In 1895, an Evansville boy, Charlie Dexter, returned to his hometown after studying two years at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. Charlie was drawn to theatrics and the stage at an early age and was frequently seen in local minstrel shows around the Evansville, both before and after his return. When he came home from college, Dexter took a job as society and drama editor of a local newspaper, the Evansville Blotting Pad. He also took a job with the 1895 Evansville Blackbirds as a leftfielder, where he batted a respectable .288 for the home team. He missed the controversial late season collapse, when the Blackbirds were accused of throwing Southern League games (full story in my book). Charlie avoided that imbroglio when he was sidelined with a broken finger, after falling from a streetcar.

In 1896, Dexter was lured to Louisville to play for the Colonels in the National League, not as an outfielder, but as their full-time catcher. Charlie was as versatile on the baseball field as he was in his other life ventures. When his eight-year major league career ended at the end of the 1903 season, Charlie had played every position in the field at one time or another. He is still the only major league player to appear in more than 300 career games and play at least 10 percent of those games at each of the five infield positions. Charlie’s versatility was never more evident than off the diamond on December 30, 1903.

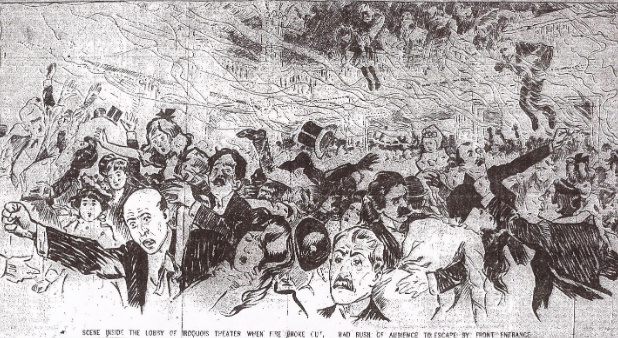

On that afternoon Charlie and retired baseball friend, Frank Houseman, were sitting in Chicago’s Iroquois Theater watching a matinee of “Mr. Bluebeard,” a musical comedy starring Chicago’s Eddie Foy. Dexter and Houseman were accompanied by their wives, children and other family members. Most of the estimated 1,700 in attendance at the Iroquois were mothers, teachers and children enjoying their winter break from school. As the second act began, drapes above the stage caught fire from a nearby arc lamp. When it became clear that the flames could not be contained, audience members fled from their seats toward what few exit doors they could find, but most doors were obscured by curtains. Many were trampled as the scene became one of dire panic. Performer Foy stayed calm and from the stage implored those in attendance to exit in order, before he finally escaped through a sewer hole under the stage.

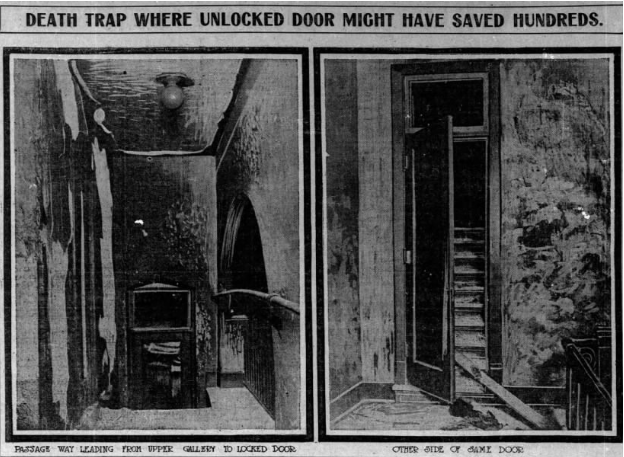

Charlie Dexter and friend, Houseman, remained calm. Searching through the smoke they found two exit doors behind the curtains on the north side of the theater, forced them open, and cleared away bodies to create a path out of the burning building. The two ushered as many as 300 patrons to safety through the exit before finally fleeing themselves. Both made it out safely. They later downplayed their heroics. An estimated 605 didn’t survive the Iroquois Theater fire, making it the deadliest single-building fire in U.S. history. It could have been worse had it not been for Charlie Dexter and Frank Houseman. Two ballplayers. Both played the role of hero.

Artist’s depiction of the Iroquois Theater mayhem.

Although 1903 was Dexter’s last in the major leagues, he continued playing organized ball, mostly in Des Moines of the Western League. In 1905, Dexter was with Henry Quait Bateman and some other baseball friends enjoying a night on the town. Bateman was with Milwaukee of the American Association at the time. After quarreling with Bateman over cab fare, Dexter was said to have stabbed Bateman, puncturing his lung. Bateman was rushed to the hospital and was greeted with a dire prognosis. Although nearly pronounced dead, Bateman made a full recovery and never pressed charges against Dexter. Bateman went on to outlive Dexter by three years.

Charlie Dexter left baseball after the 1908 season. He spent some of his later years writing baseball articles until, in 1934, he committed suicide by gunshot in Cedar Rapids. Why he took his life is still a mystery. The Evansville native was 57 years old.

Leave a Reply