My second book has gone to print, so I’m back with more of what didn’t make my first book (see Books section).

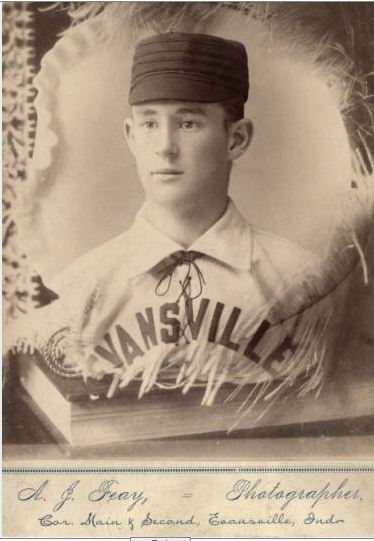

I devoted a short piece in my first book to this young phenom, who pitched a no-hitter for the Evansville Hoosiers at the age of 15 in storied old League Park on Louisiana Street (read the game account in the book). But there was much, much more to tell about this boy/man. Let’s go on the life journey of McGill after his short stay in Evansville.

William Vanness “Kid” McGill was a third generation Irishman and was truly a kid when he started his professional career with Evansville during the 1889 baseball season. He was born in 1873 in Atlanta Georgia, the son of a railroad agent. Willie was possibly the first teenage sensation to play minor league baseball. He was often referred to as “the boy wonder.” He was listed as five-feet six-inches tall and weighed 170 pounds during his tumultuous baseball-playing career.

Not all good for the Kid. The problem with Wee Willie was characterized by newspaper accounts of the period. He loved “high living” and was “undisciplined.” Contemporary baseball writer Bill James once listed McGill as one of “The Drinking Men of the 1890s,” a title earned by players known for their heavy alcohol consumption. While playing for Cincinnati in 1891 he was taken under the wing by Reds pitcher Ed “Cannonball” Crane. Crane was not a good influence on the youngster. Both players had run-ins with the Cincinnati police, the most publicized of which occurred in April. The duo was “out to sample some of Kentucky’s staple” and got into a tussle with a store employee. When that man retreated, the two started throwing ash barrels and boxes at each other. The Cincinnati police intervened and carted them off to jail. The next day they were fined over $100 “for the night’s fun,” wrote local papers.

Word of Willie’s behavior got back to his father, Thomas, in Chicago. Upon hearing of his son’s misdeeds, Thomas McGill hopped on a train from the Windy City to “right matters.” The elder McGill was closely involved in Willie’s career and acted as contract negotiator for his son. The train carrying Willie’s father crashed outside of Indianapolis, injuring the elder McGill. Thomas McGill died ten days later in an Indianapolis hospital from a “concussion of the brain” sustained in the mishap. In announcing Thomas McGill’s death, the Evansville Journal noted that Willie’s father had made many warm friends in Evansville and was a frequent visitor to the city.

Just after the wreck Cincinnati decided it had seen enough of Willie. During his father’s hospital stay the youngster was released to the St. Louis Browns, owned by Charles Comiskey. There he got into more trouble. McGill was soundly beaten in a late-season scuffle with Comiskey. The soon-to-be famous owner said Willie got the whipping because he “barked up the wrong tree”. That ended his tenure with the Browns. Remarkably, Willie won 20 games in the turmoil-ridden season. He was just 17-years-old.

After appearing in only three games for Cincinnati in 1892 reports emerged that Willie had reformed himself. The Chicago Spiders of the National League signed him in January 1893 after learning that the wife of a Wisconsin-Michigan League official had cured him of his bad habits. “His conduct was exemplary all winter,” wrote the Chicago Tribune. There were other problems.

Malachi Kittridge, catcher for the Chicago Spiders, told the Buffalo Enquirer in 1905 that his father’s passing explained some of McGill’s lapses during his first year in Chicago. For some time after the accident, Kittridge explained, Willie believed that his father haunted him, particularly on trains. One night while traveling McGill climbed into Kittridge’s sleeper car bunk “shaking with fright” and smelling “like the backyard of a Kentucky distillery.” Wee Willie thought he had seen a ghost. Then something brushed by the curtains of the bunk. Willie lashed out with both feet. It was the train porter. Willie sent the porter flying, shattering glass and waking everyone in the sleeper. One of those he woke was his manager, Cap Anson. Anson fined him $100 and deducted money to pay for damages from the pitcher’s paycheck. That was not the first or last time Willie and Anson butted heads. McGill still tacked up 17 wins for the Spiders as a 19-year-old.

McGill’s last major league stop in 1900 reacquainted him with Comiskey, then head of the Chicago White Stockings. The Chicago owner wanted to sign Willie but his offer of $160 per month wasn’t to the pitcher’s liking. Comiskey blamed McGill for criticizing him in numerous newspapers. When McGill went to Comiskey’s office to talk about the offer the owner reportedly threatened McGill with violence. Later, when cooler heads prevailed, McGill signed the contract. In six games with the White Stockings the lefthander won three and lost two. It was the Kid’s major league swan song.

The major league end came quickly for McGill due to a sore arm and his clear propensity for late nights, poor training and disagreements with management. His big-league career virtually ended in 1896 at the ripe old age of 22, not counting the White Stockings stint. During six years in the big leagues, he played for Cleveland (Players League), Cincinnati (American Association), Comiskey’s St. Louis Browns (American Association), Chicago (National League) and Philadelphia (National League). His major league record was an unspectacular 72 wins and 74 losses. Some early accomplishments remain in the Major League record books after more than 120 years. Willie is still the youngest with a complete game, a shutout, and 20 wins in a season.

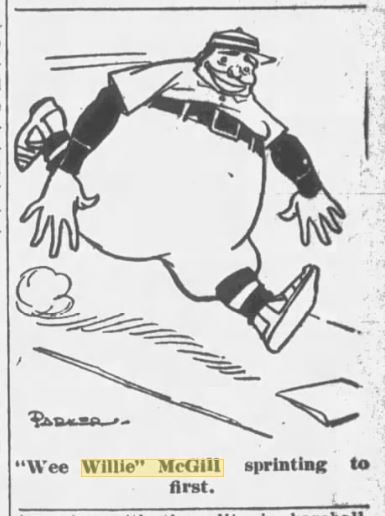

By 1912 McGill had grown rather portly. Cartoons showed him as a rotund, but still effective hurler for the semi-pro Chicago Spaldings. After witnessing McGill toss a fine game against a St. Joseph, Michigan team, a Chicago Daily Press writer penned a poem that started like this:

Wee Willie McGill is a tough little pill,

No longer a kid, he’s too small to be Bill.

He’s as big north and south as he is east and west,

And his portside flinging is some of the best.

Willie’s ties to the Hoosier State were not confined to his Evansville stints. He pitched for Notre Dame University’s first varsity baseball team in 1892 when the rules around collegiate eligibility were not firmly established. To be more accurate, the rules were whatever got the job done. Other accounts say Willie attended the school in earlier years. This time he was a professional. Willie struck out 12 batters in a 6-4 Notre Dame win over Michigan. That Irish team, for that game, included seven big leaguers, purportedly brought in specifically to exact revenge on the University of Michigan. The Notre Dame baseball victory avenged a stinging 8-0 football loss to the Wolverines in 1887. Michigan trounced the South Bend school by two touchdowns at a time when crossing the goal line was worth four points. Revenge, at any cost, was sweet for the Irish.

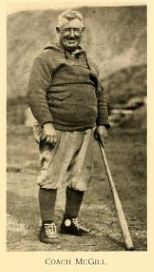

Later in life the Kid’s career turned collegiate and built a career from it. McGill credited legendary coach Amos Alonzo Stagg for getting him his first job in training and coaching at the University of Illinois. He served as athletic trainer there from 1910 to 1913, also filling the role of freshman basketball coach and assistant baseball coach. He moved to Northwestern University in Chicago for 1914 to serve as an athletic trainer and spent one year as the Wildcat’s head baseball coach, leading them to a 4-4 record in 1919. In 1920 Willie served as trainer for the George Halas’ Chicago Staleys football team. That team later became the Chicago Bears. All the while, he still dabbled in the semi-pro baseball leagues of the area. Aside from athletics, McGill was known to have business interests in the Chicago area.

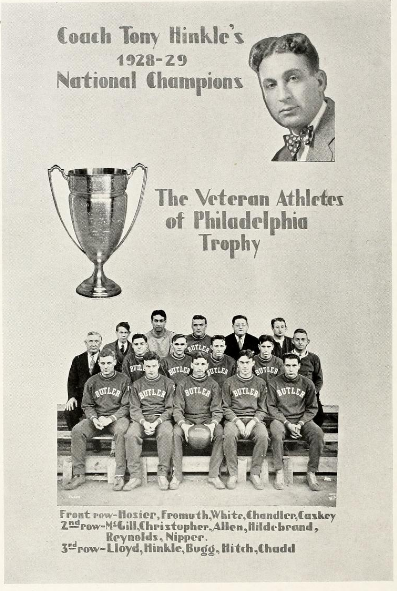

Willie ended up back home again in Indiana when an Illinois alumnus, Potsy Clark, was named the Athletic Director and Head Football Coach at Butler University in Indianapolis. Clark brought Willie in as the Bulldogs athletic trainer in 1927. McGill then took Butler legend Tony Hinkle’s place as head baseball coach for the 1929 and 1932 seasons during the short time Hinkle was removed as the school’s A.D. and football coach. Besides his time as baseball coach, Willie served exclusively as the trainer for the athletic department. He is pictured in numerous team pictures in the school’s yearbook in that capacity, including Butler’s 1929 National Champions Basketball team, coached by Hinkle after the Butler coaching icon was relegated to mentoring just the roundball teams during the Clark era. Later, Willie appeared in a photo of the 1931 Butler Football team with President Herbert Hoover at a visit to the White House in his capacity as trainer. During his time at Butler McGill served as trainer for high school basketball teams playing in the state finals at Butler Fieldhouse, among other events at the famed venue.

McGill ended his two-year Butler baseball coaching career with a 13-9-1 overall record. Accounts from The Drift, Butler’s annual yearbook, portrayed Coach “Wee Willie” McGill as a beloved mentor and trainer for every athletic team. The yearbook referred to his Butler baseball teams as the “McGillmen.”

After his Butler University years “Kid” McGill stayed in Indy and worked for Indianapolis Power and Light and later American Compressed Steel Corporation. He died in 1944 and is buried in Indianapolis’s famous Crown Hill Cemetery, alongside many Indiana luminaries. That list includes President Benjamin Harrison, Eli Lilly (of drug-making fame), Booth Tarkington, James Whitcomb Riley, Fred Dusenberg (of automobile fame), and Ovid Butler (founder of Northwestern Christian University, which is now Butler University). Crown Hill also contains the coffins of infamous characters like John Dillinger.

Leave a Reply